"A great photograph is a search for meaning. It asks questions that lead to a lot of other questions."

And so started a weekend adventure in identifying personal inspirations and motivations for the twelve photographers in Susan Burnstine's workshop Visual Narratives given this weekend at Lúz Gallery. In many ways, that lead statement was prophetic for the work we did in this class, because to make great photographs really requires that an artist understands what meaning they are searching for and that they are most strongly connected to. And finding out what that is for each individual involves asking questions that in turn lead to many more questions. It involves looking at each person's work and asking questions that dig deeper and deeper for meaningful answers.

If that sounds intimidating and raw, the kind of deep introspection that you've avoided because it makes you uncomfortable and wiggly, you're getting the right idea. It's the magic of Susan and the workshop that she's developed that you will, with her guidance and the help of your fellow workshop students, drill down and find true understanding of what you are strongly drawn to, what meaning that has for you, and how that informs the work you've done and can even more strongly inform the work that will come.

I think it's fair to say that for all of us the realization at the beginning of the workshop that this was what was in store for us was at least somewhat frightening (or a whole lot of frightening). Through careful structuring of the progression of activities in the workshop, and by being very open, genuine, caring and quietly relentless, Susan helped guide us through this daunting task. Sure there was some resistance, sure there were a few tears, but there was also a lot of laughter and good will shared by all of us, and that sense of going through something together that made for an incredible experience from which each of us will grow as artists.

I find myself reluctant to talk about the process we went through during the workshop, not because it was so traumatic (it wasn't). Although we all did the same exercises, there was enough attention given to the specific needs of each individual during those exercises that each of our experiences was unique. This was not a cookie-cutter, "one size fits all" workshop - each participant was given the time, energy and level of inquiry that was appropriate for where they are in their development as an artist. Each person had the support and help of all the other participants during each stage of the workshop. It was an incredible group of people from diverse backgrounds who contributed an astonishing array of information and insight as we talked about the current work each person showed.

In my own case, I feel that I left the workshop with a greater understanding of what is driving my photography, what deep meaning I'm connecting to and searching for in my images. I learned a great deal about how key inspirations are the foundation upon which I have, and can continue to build my own visual language. With Susan's help, I identified some key words that succinctly connect me to that deeper meaning of my work, that I can use as cues when going on to make more images. There were also suggestions from Susan of other artists that will act as further inspirations more closely related to the deeper meaning that informs my work. We were also introduced to the work of some of the most important storytellers amongst current contemporary photographers that will serve as a reference from which we can draw wisdom and inspiration for some time to come.

I have to admit that I don't feel what I've written comes close to doing justice to how great this workshop was. I've found it difficult to put into words what this experience has meant for me. I can say that as a teacher myself, I was in awe of Susan's unwavering commitment to each of the students, her generosity in sharing her experiences and knowledge, her discerning eye and ear and the empathy she had for each person during the process. If you have the chance to take a workshop with Susan, don't hesitate for a second. It will definitely change your life as an artist in the best possible way.

Another important factor in the success of the weekend was the wonderful environment created by the fine people at Lúz Gallery. Quinton, Melissa and Tom made sure the workshop ran smoothly and were wonderful company during the weekend. I've been quite fortunate this year to take four outstanding workshops at Lúz - wet plate with Joni Sternbach, photopolymer gravure with Don Messec, marketing with Lauren Henkin and now visual narrative with Susan Burnstine. Each workshop lead by not just a knowledgeable expert, but also an outstanding teacher who offered an outstanding experience. Thank you Quinton and Diana for your vision in bringing such consistently high quality workshops to my little town, and thank you to Melissa and Tom for helping to create that welcoming environment.

Monday, December 5, 2011

Wednesday, November 30, 2011

Influences and Inspiration

I'm going to be taking a workshop at Lúz Gallery this weekend entitled "Visual Narratives", given by Susan Burnstine. In preparation for the workshop, we were asked to put together the following: a series of 10-20 images to discuss in the context of visual narratives, an image that best represents ourself (!), and one or more images that inspire us. I don't know how the other participants are finding the preparations, but at first I was a bit stumped by the second and third items. It took a while for me to realize which image best represents myself, and as I thought about inspiration I started to think outside photography. In this post I'm going to share some nascent thoughts on how artists working in mediums other than photography have influenced and inspired the work I do (and aspire to do) in photography.

Helen Frankenthaler

"Sill life with carp" E. Manet "To e.m." H. Frankenthaler

In the work on the right, Frankenthaler used the colour palette of Manet's still life, but she broke down Manet's composition to its most fundamental base - the distribution of colours and tones, thus transforming the classical still life into something far more emotional. This type of transformation is something I strive to produce in my photographic work.

Pat Steir

Helen Frankenthaler

"Message from Degas"

I have long been a fan of Frankenthaler's work in etching and lithography. I picked this image because I learned a lot from it about proportions within space, the use of fine line to create contrast to large masses in a way that activates the composition, and most importantly that rules must sometimes be broken for the sake of composition. In this image, there is a large mass of darkness coming from the top of the frame. Our natural inclination (and one of the "sacrosanct" rules of composition) is to place such a large, dark mass at the bottom to "ground" the image. Sticking to the rules would not have produced such a strong, compelling work and would have decreased the sense of flow we feel in the yellow ground.

In the work on the right, Frankenthaler used the colour palette of Manet's still life, but she broke down Manet's composition to its most fundamental base - the distribution of colours and tones, thus transforming the classical still life into something far more emotional. This type of transformation is something I strive to produce in my photographic work.

Pat Steir

Starry Night: August

I've taken away several lessons from the prints and paintings of Pat Steir. If you look at this image, you can sense that it continues beyond the confines of the frame, which engages your imagination as you actively "fill out" the image. I learned that you can have an image that uses mostly dark tones with bright highlights in a way that doesn't feel high contrast but convinces you that you are looking at a normal scene with a full tonal range. The pattern in this image is random, but reads as if there is an order to it, one that can be discerned with further consideration. I also like the light pattern on dark because it makes me aware of the patterns of lichen and erosion on the coastal rocks where I live.

Richard Diebenkorn

"Cityscape"

"Ocean Park"

I've learned a lot from Diebenkorn about geometry in the landscape, how it can be used to create effective compositions (e.g. Cityscape), and not to fear having a large open space within a composition. Look at that huge expanse of blue in Ocean Park and imagine creating a photographic composition that crowds the contrasting elements into a small part of the overall image. When you look further, you realize this isn't minimalist to the point that we have basically a horizon line that fails to meet the "rule of thirds", but otherwise divides the space into two bands of tone - this composition contains several geometric and colour elements within that thin band at the top, that counterbalance the huge expanse of blue and are bold enough to hold our attention.

Gerhard Richter

"Drawing, 1999"

Drawings like these by Richter have taught me a lot about the importance of placing elements within a composition, about the importance of how the elements relate to each other, and about how information is transmitted to the viewer by these elements. Looking at this drawing, I can easily see a marsh scene, the shore with grass on the left, reeds in the water on the right. Looking at this makes me realize that artistic intent doesn't have to be sacrificed for clarity; the viewer can extrapolate from partially visible elements in either a dark or high key image to interpret the scene portrayed. Looking at this drawing makes me think of images of blade of grass in fields of snow made by Harry Callahan.

"Hanged"

Richter is famous for his blurred, photorealistic paintings. This one is made from a newspaper photo of the body of Gudrun Ensslin, a founder of the Red Army Faction, who hanged herself in prison. For me, the blurring represents a truth about photography - that it can never convey the absolute truth. Of all the visual arts, we turn to photography as the purveyor of unvarnished fact. Yet it can never fulfill that role - the person who took the photograph has made decisions about composition and lighting that blur the facts, at least a little bit. The facts are blurred further by the viewer, who rarely looks upon an image in a completely dispassionate way, but brings interpretation and opinion to that viewing. Again, there is a slight distortion of fact. Add onto that the collected viewing by many people and the resulting polarization of opinions about the image, and then the truth is blurred further, just as Richter has shown in this painting. I find this idea freeing, because I don't have to feel that as a photographer I'm constrained to make images that are completely representative of a set of facts that are before me. I can be free to interpret what I see and make art rather than just a photographic record of facts.

Richard Serra

"Sequence"

"One Ton Prop (House of Cards)"

I've learned a lot from the sculpture of Richard Serra about how objects not only occupy space, but also define space. The lines defined by the edges of the materials that he uses have made me look for edges and lines that "draw" objects and spaces in my photographic compositions. Serra also draws and makes prints, and it's interesting to see how he visualizes the transition of his three dimensional ideas to the two dimensional medium of drawing, just a photographer must visualize representing the three dimensional world in a flat object:

"Splines"

Edoardo Chillida

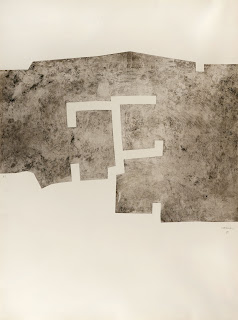

"Euzkadi V"

"Gravitation"

Chillida is another sculptor who also worked in drawing and printmaking. When I look at his work, I'm inspired to consider how I will produce the final work from my photographic practice. In the Euzkadi print, it is interesting to consider how he placed the image on the paper, how those decisions become part of the composition and define a larger space. In Gravitation, materials are layered, with cut outs to define space and spatial relationships as well as mark-making to distinguish different compositional elements. This work inspires me to question whether photographs must be a single layer (I'm not thinking of Photoshop here), what might be gained by combining different materials, using cutouts to reveal only parts of an image. There's also many things to take away from this work in thinking about making artist's books.

Sunday, November 20, 2011

IMPRINT: Opening from within

I was at the opening of the show IMPRINT at Lúz Gallery this

afternoon. Here are some of the comments people shared with me:

“I love the way the

images relate to each other.”

“The work has a really

cohesive quality, a real strength.”

“There’s a great flow

to this show.”

You might be thinking from those comments that IMPRINT is a

solo show. It consists of the work of eight photographers who are, in the words

of the gallery owners “artists who have made a lasting

impression on us during the last 12-months.” A group show with such flow and

cohesiveness it gives the impression of being a solo show? Yes, thanks to the

skill and talent of the curator, Diana Millar. I am very fortunate to be one of

the artists included in this show.

Millar and her partner Quinton Gordon are consistently

presenting work at Lúz Gallery with the intention of not only putting

outstanding photography before viewers, but doing so in a way that transforms

how people think about photography. As someone else said to me at the opening:

“I always love coming

to this gallery, (and I apologize if this seems like a backhanded compliment),

because I know what I’m going to see is art, not just photography.”

In putting together a group show that has a sense of

cohesiveness with high visual impact, a talented curator like Millar must bring

together several elements. The first important one is image selection, looking

over the work of the different artists and selecting the strongest images from

each. At some point in this process, consideration has to be given to how the

images from different artists might relate to each other, although subjects,

process and visual approaches are going to differ. Eventually this leads to

designing the show itself, planning how works will be hung in the gallery space

to create a natural visual flow that creates that sense of cohesiveness.

In the case of IMPRINT, Diana successfully brought together

the dreamscape images of Susan Burnstine, panoramic views of seashore and sky

by Karen Curry and abstract light sketches by Gillian Lindsay in one physical

zone of the gallery. From this description it might not seem that these images

would relate to each other, but they share a lyrical quality and give the

viewer a sense of passing from a internal view (dreamscape) to the external

view (panoramic widescreen) to an almost subconscious view of the abstract

light patterns. What I loved about this grouping of images was the way it

invites inquiry – as a viewer you sense the flow and relationship between the

works of these three artists before you can articulate why that flow exists.

The role of process in Gillian Lindsay’s work provides a

nice bridge to the second zone created by Millar within the gallery space,

where lumen prints from my series Taxonomy were hung along with the Surfland

series of wet plate collodion tintypes by Joni Sternbach, the Polaroid images

of Sea Life by David Ellingsen, the hand annotated landscape images of

Lyndia Terre, the soft focus images of a fishing village by Jan Gates and the

Mile Zero images by Quinton Gordon. Once again there is a nice flow and

interplay between these diverse works, with an underlying link of

documentation: of plants (Taxonomy), a closed culture (Surfland), biodiversity

(Sea Life), mapping the landscape (Terre), of a disappearing culture

(fishing village), and of the daily landscape (Mile Zero). Although the

different processes used were quite diverse, from one to the next there was

always at least one shared characteristic, which leads the viewer not only to

connect process to process, but also to think about how each subject matter is

best served by one process over others.

Usually openings are mainly social events held in the dark

of night, where friends and family come to support the artist(s). They are

characterized by being overcrowded, making viewing of the actual work

difficult. Most of the time people stand in groups chatting, their backs to the

art work. This afternoon’s opening was a welcome change from this norm. Held on

a sunny afternoon, the work was shown to its best advantage under natural

light. There was a steady flow of people, and while there was socializing for

sure, I noticed that a lot of people looked carefully at the work, talked about

it, considered it, and then went back two or three times to look again. The

strength of the work drew them in the first time, but it was Diana’s excellent

work as curator that created the flow and cohesiveness that brought them back

to consider further the work again.

Check back with the Lúz Gallery website for photos of the

installation and opening. I apologize for not including any here, but from the

start of the opening to the finish, I was completely immersed in the experience

and gave no thought to taking photos myself. It is a deeply engrossing show –

if you are in Victoria or can find a way to get over before December 22nd,

I hope you will come and see the work.

Saturday, November 12, 2011

Stepping into the Abyss

Last night I listened at Lúz Gallery to an artist

talk by photographer Dan Milnor, that was very personal, very insightful and

very thought provoking. It was as much about his journey as an artist as it was

about the art that he’s made, a journey that has caused him to question

everything he thought he knew about being a photographer.

Milnor had a successful career as a

commercial and fine art photographer, when around fifteen years ago he became

tired of the demands of commercial photography and took a job with Kodak. The

job required him to sign a non-competition agreement, and in return as a Kodak

employee Milnor had access to as much film and processing as he wanted to

pursue his personal photographic projects outside of work. Released from client

demands, his personal photography took off and he had the freedom to plan

specific long-term projects that sometimes took years to complete. The talk

began with a slide show of work from a project on the Easter pageants in remote

villages in Sicily. Paired with haunting music, the images had power and

strength. This project, and others he undertook in the same time period were

very focused and planned, with the intention of generating images for

exhibitions and potentially books. At the end of his fifth year of working for

Kodak, Milnor had amassed several bodies of work that impressed other

accomplished photographers. At this point Dan had an epiphany, equating the

freedom he had from working for clients with the ability to focus on and

produce excellent personal work. Having had that epiphany, Milnor left Kodak

and once again became a commercial photographer.

Ten years later, Milnor sensed

something missing. The first hint was a decision to visit a friend in Panama

and to take some pictures, but to just take “snapshots” rather than doing a

specific, focused and well planned project. He found the experience somewhat

surreal, in the sense that he was more aware of all that was around him, and he

made images of whatever attracted his attention. It went against the grain of

how he’d worked before, and how he’d been trained to work and to think about

making photographs. After the trip, Milnor edited his images and created a book

using the print-on-demand service Blurb. Another part of the puzzle to his

growing unease with his commercial photography career came one day while he was

at home, watching planes take off from John Wayne Airport. He was thinking how

he should be on one of those planes, going somewhere else to make photographs,

when he realized that a decent photographer should be able to make good images

wherever they are, including at home. Thus began the project “Homework”,

defined only by restrictions on locale and how many exposures on film he would

make at any given time. The resulting images are abstract, raw and very engaging

and again he self-published them as a book for his own reference, considering

the images as something of meaning only to himself. It was during a visit to a

local art broker to deliver work from another series that he learned to his

surprise that the Homework images were ones that the broker felt would be easy

to place with clients.

So these two personal projects

developed more organically, with virtually no planning compared to his previous

personal projects. Dan had really not planned a specific outcome for the work,

nor did he necessarily see it as having the wider artistic appeal of his more

focused work like the images from the Sicily project. I think one might be able

to describe these last two projects, and how they worked out, as a second epiphany

of sorts as Milnor continued to consider the impact of being a commercial

photographer. It was at this point that the offer of a full-time position as

Photographer at Large with Blurb dovetailed with a decision to once again stop

being a commercial photographer.

Dan turned his attention to his

abiding interest in the “wild west”. He grew up on a ranch in Wyoming, and has

been fascinated with the remaining vestiges of the past history of the frontier

ethos that exists today in states like New Mexico. His current working project

is “The New Mexico Project”, and it started out as a planned, focused project

in two parts, the first being “Wildness”. After working on the project for

awhile, Milnor was driving from LA to New Mexico, his mind filled with ideas

and thoughts about how the project was developing, how to pull images together

for an exhibition or book, when he realized that he had been passing through an

interesting landscape that he was completely ignoring. He reflected on the fact

that the Panama and Homework projects, lacking such specific focus, had allowed

him to be much more aware of everything around him at any given moment. This

realization lead to the third and final of his epiphanies, and it was the one

that caused Milnor to turn his back on the concerns of the photographic

establishment with respect to what defines a project and what are the desired

outcomes of a project. It also completed a long, slow process by which Milnor

unlearned the patterns of thinking that go along with those concerns.

This was the point where I felt

that I was no longer listening to a great, articulate artist’s talk, I was

listening to something unique and very special. Because Dan Milnor, after years

of being a successful photographer by just about anyone’s standards, threw out

everything he knew about being a successful photographer and asked himself the

critical question “What does photography really mean to me personally?” It was

at this key point that the lessons learned from the Panama and Homework

projects came together to change the direction of the New Mexico project.

Milnor found himself in northern

New Mexico where he slowly worked at being accepted in a small town that didn’t

see many gringos. He began photographing the farmers and then other members of

the town, some who have never been photographed, and have never held a

photographic print in their hands. He wasn’t sure what the outcome of the

project would be, but he realized that the people the project was arguably most

important to would be the least likely to see the finished work – that is,

those he was photographing. His sole concern about the outcome of this project is

how he can engage the subjects of this project with the work itself. Dan would

like them to be able to see and interact with the work, and to contribute their

thoughts and impressions on what it being photographed means to them. This is a

project outcome that lies well outside the understanding of the current

photography world.

Dan described how he’d photographed

a farmer who had never had his photograph taken before, who had never used a

computer. The farmer’s wife showed him his photograph by lifting the lid of the

laptop, where the first thing he ever saw on a computer was a photograph of

himself. In this day and age of “Photography 2.0 on the Web” etc, it’s almost

unimaginable. It’s not difficult to see a parallel between a subject seeing an

image of himself for the very first time, and a photographer who has walked

away from one understanding of what photography means to search for a different

understanding.

I sense that Milnor’s desire to

hear from his subjects about their experiences of being photographed and how

having prints of their images has brought that experience into their lives, is

tied into his own query about what photography, and being a photographer, means

to him. It’s a shared journey between photographer and subject, a way to deepen

further the engagement between the two. By approaching this project in a

completely unstructured way, with no particular destination in mind, Milnor has

taken the proverbial leap of faith, and stepped off into the abyss.

In one of those odd quirks of

synchronicity, this morning I started reading a book that’s been on my

nightstand for a while. It’s “A Field Guide to Getting Lost” by Rebecca Solnit.

In the very first essay, Solnit writes “Leave the door open for the unknown,

the door into the dark. That’s where the most important things come from, where

you yourself came from, and where you will go.” She goes on to recount an

experience she had while giving a workshop, when a student came to her with a

quote from the pre-Socratic philosopher Meno “How will you go about finding

that thing the nature of which is totally unknown to you?” Solnit goes on to

write that “it is the job of artists to open doors and invite prophesies, the

unknown, the unfamiliar; it’s where their work comes from…”

Sunday, October 30, 2011

Liberation

Today I'm writing about liberation - from the tyranny of a bad back, from the tyranny of always having to have a reason or plan to make photographs and from the tyranny of self-contained compositions.

Today was the first time in a couple of weeks that I've been out and about in the forest after I seriously put my back out. It was glorious to be back outdoors, walking comfortably and seeing things with fresh eyes.

There have been plenty of times that I plan to go walking the trails, and find myself leaving the house hours later than I had intended. So often the delay is related to trying to decide which camera(s) I want to take with me to which location(s); deciding between digital or film or both; black and white or colour; etc etc. This morning I felt a strong urge to shoot some film, but I had a stronger desire to get out and it was liberating to just grab my little Canon compact digital camera. More important to get out walking with any camera than get frustrated by having to make decisions. And the choice was perfect for the purpose - I didn't have a specific plan in mind for what images I wanted to make, rather I just wanted to be able to document my enjoyment of the walk as it unfolded. I think this represents the most basic, fundamental motivation I have for making images - to help me record what I see and by doing so sharpen my eye to what is right before me.

Before I went out to the forest, I stopped in at Lúz Gallery to visit with my friends Diana and Quinton, with whom I've had many enlightening conversations about art. I enjoy these visits for many reasons; it's refreshing to see photographs that are physical objects, to consider the choices the artists have made with respect to size, materials, presentation and to consider why some images are more compelling than others. While talking with Diana and Quinton today, we shared a number of ideas about composition as it comes into play with single images, series of images, and book design.

In many ways, I'm glad that I did not return to photography as a medium of expression before first taking detours through papermaking, printmaking, painting and drawing. Every step of the way I learned valuable lessons about composition. One key idea that I always keep in mind is that the image should not be composed so that everything is within the frame but rather it should be composed to give the sense that the image continues beyond the confines of the frame. In most instances I want the viewer of my images to start somewhere within the frame, and follow the visual cues to the edges of the frame and then beyond the frame. Requiring the use of the viewer's imagination to complete the image beyond the frame results in a level of engagement with the image and an expanded experience of the photograph. Thinking about this now, I understand why I often make square images - without the cue of a "landscape" or "portrait" orientation of the rectangular frame, there's less chance that the image will be constrained by the frame itself, and less chance that the viewer's imagination will in turn be constrained.

Sunday, October 2, 2011

Night Rituals

I've been thinking quite a lot lately about my affinity for the landscape, one that I formed at a very early age. As a child I spent many summer days on my own exploring nearby woods, fields, ponds and streams completely at ease with my solitude. I seemed to find little spaces that were interesting and comforting, and to this day when I go out to photograph the landscape I rarely look for the big vistas, but continue to seek out these small, intimate spaces.

So as I went out for a walk this evening, I took my point and shoot just to exercise the creative muscle. At first I had the intention of making some motion abstracts down by the sea (and I did subsequently do that). But as I was walking along, I began to think of how my interest in small, intimate spaces in the woods might be expressed on a walk in the neighbourhood.

And so I kept my eyes and mind open to little spaces with a faint glow of light. As the winter draws near and nightfall comes earlier, walking in the evening is really all about that interplay between the somewhat cold, depressing darkness and the comforting light that peeks into shadows and comes as a glow from the windows of the homes.

So there I was, walking and looking - around, down and up - making images in the fading light as best I could. I like what these images say about the neighbourhood this evening and how well they reflect my experiences on that walk.

Tuesday, September 13, 2011

New directions (no, I have not joined the glee club!)

For the past couple of years, when I've gone out to the local forests and beaches to make images, I almost always carried a Holga or (original) Diana camera with me if I was intending to expose some film. Like many before me, I became enamoured with toy cameras, slowly acquired a few different ones, hung out at toycamera.com and subscribed to LightLeaks magazine. I found fellow enthusiasts at sites like Flickr, devised a few modifications of my toy cameras, submitted images to "plastic lens" shows and life was fine in the blurry world.

It took me a while to figure out how using toy cameras would fit into my photography practice, and eventually I created two bodies of work that combined narrative with landscape. One is "That summer at the lake", which I discussed in a recent post. The other is "My beloved rises from her sleep" in which the images stood as metaphors for lines from the poem of Mahmoud Darwish. I also have in my flat files a couple of nascent series of toy camera images from the local oceanic coast, and I'm in the (slow) process of turning some Holga images I took last fall in San Francisco into a zine.

It took me a while to figure out how using toy cameras would fit into my photography practice, and eventually I created two bodies of work that combined narrative with landscape. One is "That summer at the lake", which I discussed in a recent post. The other is "My beloved rises from her sleep" in which the images stood as metaphors for lines from the poem of Mahmoud Darwish. I also have in my flat files a couple of nascent series of toy camera images from the local oceanic coast, and I'm in the (slow) process of turning some Holga images I took last fall in San Francisco into a zine.

I remember her reflection in the early days,

when lightning crowned her forehead

from the series "My beloved rises from her sleep"

But recently I've been thinking about trade-offs. While I feel I used the toy cameras effectively in creating these narrative streams, I've also come to realize that this aesthetic adds another layer between me and my experience of that moment as it also does for the viewer. While the toy camera creates a sense of a dream-like or memory state it also distances the viewer from the actual "in the moment" experience. I remember a while ago musing in an e-mail conversation with a friend about this conundrum and writing to her that I wanted to explore the differences in narrative landscape images created by the toy camera and a high end optical lens. This idea has been percolating in the background for some time, and while that's been happening I've found myself drawn to work by other photographers that at first view might seem to be images of the mundane, but on further reflection is better defined as acute observation of what is right in front of us all the time, a documenting of actually living each visual moment.

It's been a while since I've walked the forest with a camera; I've been working on solidifying my wet plate collodion technique in the summer months while the UV light is strong and I can work outside easily. But this weekend I felt the urge to get out with a film camera and found myself picking up my Mamiya 6. I haven't had the film developed yet, but I remembered that while I was making images with the Holga for the "My beloved rises from her sleep" series, I sometimes carried the Mamiya 6 with me as well. So here are some images taken during the same time period as the image above. While I was revisiting these images I found myself connecting back to the moment when I made each:

Sunday, September 4, 2011

Concept, Context and the Body of Work

I've been thinking about writing on this topic for quite some time, certain that writing about how I make art is of great benefit to myself but not quite sure if such a post would be of general interest to others. Just the same, if I'm not clear on how my projects are conceived, developed and brought to finality then I'm working in the dark and asking viewers of my work to take what they see on faith. I think asking that is not fair to them, and avoiding thinking (and writing) about my process is a poor decision on my part.

Two things prompted me to take some action now. One was a thought-provoking comment Lauren Henkin added to an online discussion on the differences in viewing photographic images online vs. viewing physical photographs. The discussion was started by Andy Adams in a Facebook group called Flak Photo Network. Here's what Lauren wrote:

I think we have tendencies to try and classify - black and white vs color, film vs digital, silver versus pigment, it goes on and on. As a population in general, I think we're uncomfortable with ambiguity, with saying, "everything depends on the context." But truly, that's how I see it. There are stunning examples of people using online mediums for communicating their stories while others are using objects only. It ALL depends on how it's executed. I think if we (including me) spent more time writing about how work is executed and the merits of it both conceptually and in craft, we'd all learn a whole lot more (bold text emphasis mine)

Once I read Lauren's words, I started to think more seriously of writing about my work. As it turns out, some of my projects develop organically (i.e. there is no concept at the beginning) and others develop from a specific concept. What to write about? The answer came to me while I was reading some comments posted by Diana Millar of Lúz Gallery on Twitter after she had been to an artist talk. Diana tweeted:

Why or what is the answer that you are looking for?? Does it change your opinion of the photograph(er) if it was 2 rolls vs 20 rolls??

I found this interesting because artists often seem to be concerned with variations of this question, which in essence is how hard was it to make this body of work? I think many artists have little faith in work that comes too quickly and/or easily. Thinking about this apparent conundrum has prompted me to write about my body of work about childhood memories of summer vacations, That Summer at the Lake.

Silver gelatin prints from That Summer at the Lake

So, how did I go about this project? Well, the first "confession" is that I did not set out to make a project, much less one specifically about childhood memories of summer vacations. In essence, my art practice is largely process-driven. By which I mean that generally when I make art, everything begins with decisions about the physical process of the making: if I'm painting, I may decide to take a large piece of watercolour paper, soak it until there is water standing on the surface and begin to pour diluted paint on that surface, moving the paint around with a hairdryer to create organic lines and shapes while the paint dries unevenly. I haven't set out to make a painting of a specific image, I've set out to experiment with different ways of diluting paints and different ways of pushing them around a wet surface. As such, I choose to follow the process where ever it leads me.

With my photography practice, I'm often concerned with ways to push a method of making images. In the case of That Summer at the Lake, everything started with a question I was curious about: what would happen if I took rolls of 120 film, first making images with a Holga camera with a 4.5X6 cm mask, then re-rolled the film and made images overtop of the first exposures using a Holga with a 6X6 cm mask? I wanted to see how the imperfectly overlapping images looked, and what kind of story they might tell. So at this point, I was just setting out to try a somewhat crazy idea with no idea if the resulting film will be printable, much less interesting. Another crucial part of the puzzle was my decision to go to a nearby lake to test out this idea.

So far, this doesn't sound like much of a project (in fact the idea of doing a project was far from my mind). However, there is a very fundamental basis to much of the photography I do. I'm consumed with exploring the landscape, not it's grand vistas but the intimate spaces the landscape consists of. I grew up in an industrial steel town back east, but since the age of 8 I have spent a great deal of time exploring whatever forests, woods, rivers, streams, ponds, lakes (and more recently oceans and the sea shore) I could find near where I live. Strangely, this was just something that I was intuitively comfortable with even as young as 8. I was alone but not lonely, I was untutored in natural science and history, but endlessly inquisitive. I sought out quiet places in the woods, and there was a favourite pond I would spend hours at, catching tadpoles and bringing them home to watch them metamorphose into frogs. As I've moved around the world since adulthood, I've still sought out these places, making photographs of them and always finding comfort in them. Living on the west coast, I've become accustomed to rain forests and the shore line. But I have a special place in my heart for lakes and the woods that surround them.

So every time I go out into the landscape with a camera, these connections drive what I see and what I make images of; this in turn provides for the opportunity to produce a cohesive series of images even when everything begins with a process-driven "what if" question.

On the day this all began, I went to the lake and first made images with four rolls of film in the Holga with the 4.5X6 cm mask, choosing views and subjects that reflected my concerns and specific affinities for the lake. Everything did not go smoothly - the re-rolling of the 120 films was problematic because the end of the film is not taped to the backing paper, and tended to bunch up when I re-rolled the films. However, I carried on with the idea by overlaying fresh images on top of the exposed films using the 6X6 cm mask in the Holga. Once I developed the films, I could see they were very dense but likely printable, and I could see that there were interesting things happening from the overlapping frames.

One of the decisions I made about two years ago was to stop scanning black and white negatives in favour of producing silver gelatin prints. I am far from being a great darkroom printer, but I love making hand-crafted prints and enjoy the time I can spend in the darkroom. It was only as I started printing the images that I became excited by the possibilities for meaning that they held, and after a few prints were made I began to see a connection between what I was viewing and my memories of family vacations from my childhood.

My dad preferred a vacation where we either rented a cottage (rarely) or camped beside a lake with a sandy beach. He would sit out in the sun all day for two weeks, and I remember playing in the water, on the beach and going off into the woods to make up stories and adventures. As more of the images were printed, this connection became stronger and stronger. The physical process of producing the prints and being able to hold them as physical objects to ponder over, strengthened the meaning of the work considerably. In the end, those four rolls of film yielded 15 images that formed a cohesive body of work.

When I first saw the developed film, my inclination was to plan to make more images this way - after all, four rolls of film couldn't possibly be sufficient to produce a strong series of images. One day, four films - not possible. Yet my decision to hand-print the images instead of scanning the film slowed everything down. I work full time, so I'm lucky if I can get into the darkroom twice a month. As the images unfolded slowly during the printing process, I had the time to see the series build up and to "be" with the images. By the time the printing was finished, I completely understood that this project that wasn't a project was complete - I could not honestly see any gaps requiring new images. In fact, I have not gone back to use this method of double-shooting film for any other project so far.

Naturally, this was not the end of the process of completing the body of work. Works were titled as they brought to me fragmentary memories of those childhood vacations mixed up almost certainly with other experiences and stories I had made up for myself when I was a child. I scanned the prints, wrote a brief artist statement about the images and posted the work and statement on my website. I haven't had to make decisions about exhibiting this work yet, although I know that if it is exhibited I will keep the prints small and intimate. I suspect that the best presentation of this work will be in the format of a book that can be held and pondered over for a longer period of time.

Coming back to the title of this post, this body of work came about from a concept that was all about the process of making the images - re-exposing film, using a toycamera, using different film masks. To understand the meaning of the resulting images requires some knowledge of how they are positioned in the context of my continuing exploration of the landscape and my connection to it as a place of intimate spaces, an exploration that spans from my childhood to the present day.

Tuesday, August 30, 2011

Art needs to exist off-line

The internet is great for disseminating one's work, and it's great to learn about work being made by people you would probably never meet. I'm also learning that it's a useful networking tool within certain limits. But recent experiences confirm that for me (and others), it's important that art have a physical presence because of the ways that physicality can expand the experience for both artist and viewer.

I was recently discussing by e-mail a project that a photographer friend from San Francisco was working on, which involved taking a single subject (a tree) and exploring its form and meaning by different photographic approaches. She had initially been inspired to do so by the Wallace Stevens poem "Thirteen ways of looking at a blackbird". I suggested that she look at Jennifer Bartlett's work "In the Garden", which was a year-long project Bartlett did where she explored a somewhat mundane garden in the house she lived in for a year in France by making a series of paintings and drawings using different media, different perspectives and different scales. My friend found Bartlett's work to be helpful as her project developed, and she recently posted her first series of images as a 4X4 grid (as a working model for the presentation of the work). As we discussed the work further, I was struck by how rigid and limiting on-line presentations of images can be - there are very few decisions to be made with regard to final size of the work, differences in scale, differences in materials. We had an interesting discussion of how the impact of the work would change if it was hung as a series of installations in a gallery, with different scales, printed on different papers, some images isolated while others were grouped - all of these possibilities opening new avenues to explore the meaning of the work. Few of them are available with on-line presentation. Our discussion made me think a great deal of how these factors play into the presentation of my own work. Making the image, whether digitally or on film, is just the first step in a process that leads to the actual work whether its an online presentation or a physical one; there are just a lot more options to give meaning to the work with physical presentation.

I recently took some of my gravure proof prints and tintypes to a dinner party with friends. Two of the friends are collectors who have generously acquired a couple of pieces from me in the past. As they looked over the work, it was interesting to see how they appreciated the works as physical objects. We had an interesting discussion about the differences in scale of the gravure prints, Alex commenting that he actually preferred the smaller images that allowed him a more intimate feeling in looking at the work. Since both the 8X8 and 5X5 images were printed on 11X15 sheets of paper, this lead to a discussion of scale of the image within the scale of the substrate. As it turned out, because the gravure proofs were made in a workshop, I didn't have control over the size of paper available, and I found the discussion thought-provoking and timely as I have started printing a small series of kallitype images - what size should the image be, and on what size paper. These decisions affect a viewer's experience of the work in important ways.

During an e-mail correspondence, another friend mentioned that she really liked a tintype image I had posted on this blog of cherries in a copper bowl. I dropped in to visit with her a few days later, and brought that tintype along with a few others. It was wonderful to watch her pick them up and play with different angles of viewing them in the light. She mentioned that at first she had expected, really wanted them to be larger (the plates are 3.5 X 4.5) but that as she looked at them further she was beginning to like the smaller scale. She then went on to make a little mini-installation of 3-4 plates, which lead to a discussion of how one might display these tintypes that I found very useful. I enjoyed talking about the work with her, and learning from her reactions to the work how I might continue the project in terms of making additional images and ways to present the final work.

For me, these two experiences were far richer as a way of receiving feedback on my work, and of learning more about how my decisions on scale and presentation affect the viewer experience than any online interaction I've had over my work. It was the physicality of the tintypes and prints that were the foundation for this richer experience. I'm not about to abandon what the online platform offers in terms of interactions, broadening the audience for my work or finding interesting work by other artists. But I sense that for me and my work, that could never be enough.

I was recently discussing by e-mail a project that a photographer friend from San Francisco was working on, which involved taking a single subject (a tree) and exploring its form and meaning by different photographic approaches. She had initially been inspired to do so by the Wallace Stevens poem "Thirteen ways of looking at a blackbird". I suggested that she look at Jennifer Bartlett's work "In the Garden", which was a year-long project Bartlett did where she explored a somewhat mundane garden in the house she lived in for a year in France by making a series of paintings and drawings using different media, different perspectives and different scales. My friend found Bartlett's work to be helpful as her project developed, and she recently posted her first series of images as a 4X4 grid (as a working model for the presentation of the work). As we discussed the work further, I was struck by how rigid and limiting on-line presentations of images can be - there are very few decisions to be made with regard to final size of the work, differences in scale, differences in materials. We had an interesting discussion of how the impact of the work would change if it was hung as a series of installations in a gallery, with different scales, printed on different papers, some images isolated while others were grouped - all of these possibilities opening new avenues to explore the meaning of the work. Few of them are available with on-line presentation. Our discussion made me think a great deal of how these factors play into the presentation of my own work. Making the image, whether digitally or on film, is just the first step in a process that leads to the actual work whether its an online presentation or a physical one; there are just a lot more options to give meaning to the work with physical presentation.

I recently took some of my gravure proof prints and tintypes to a dinner party with friends. Two of the friends are collectors who have generously acquired a couple of pieces from me in the past. As they looked over the work, it was interesting to see how they appreciated the works as physical objects. We had an interesting discussion about the differences in scale of the gravure prints, Alex commenting that he actually preferred the smaller images that allowed him a more intimate feeling in looking at the work. Since both the 8X8 and 5X5 images were printed on 11X15 sheets of paper, this lead to a discussion of scale of the image within the scale of the substrate. As it turned out, because the gravure proofs were made in a workshop, I didn't have control over the size of paper available, and I found the discussion thought-provoking and timely as I have started printing a small series of kallitype images - what size should the image be, and on what size paper. These decisions affect a viewer's experience of the work in important ways.

During an e-mail correspondence, another friend mentioned that she really liked a tintype image I had posted on this blog of cherries in a copper bowl. I dropped in to visit with her a few days later, and brought that tintype along with a few others. It was wonderful to watch her pick them up and play with different angles of viewing them in the light. She mentioned that at first she had expected, really wanted them to be larger (the plates are 3.5 X 4.5) but that as she looked at them further she was beginning to like the smaller scale. She then went on to make a little mini-installation of 3-4 plates, which lead to a discussion of how one might display these tintypes that I found very useful. I enjoyed talking about the work with her, and learning from her reactions to the work how I might continue the project in terms of making additional images and ways to present the final work.

For me, these two experiences were far richer as a way of receiving feedback on my work, and of learning more about how my decisions on scale and presentation affect the viewer experience than any online interaction I've had over my work. It was the physicality of the tintypes and prints that were the foundation for this richer experience. I'm not about to abandon what the online platform offers in terms of interactions, broadening the audience for my work or finding interesting work by other artists. But I sense that for me and my work, that could never be enough.

Tuesday, August 23, 2011

Seeking Answers to an Unknown Question

from "Ten Kallitypes for a Rainy Day"

This weekend I began selecting floral images to make into a series of kallitype prints. I started with ten images which I had previously made during my "Daily Practice" exercise from last year, and converted them into digital negatives for printing. Yesterday when it was raining and I didn't feel like going to work, I played hooky and made small proof prints of the negatives. Although the finished body of work will be more than these ten images (and the final prints will be on larger sheets of paper), I quickly sequenced the images and began internally referring to them as ten kallitypes for a rainy day. You can see the complete series of images at the end of this post.

But something odd happened during this process - I began to feel a bit of uncertainty and anxiety about this series, which I've been trying to puzzle through. For one thing, it was a different way of working for me - I usually have some objective or definition in mind at the start of a project (although that may change as things progress), but in this case I was pulling images together from an archive. So the working method here was different, and perhaps explains part of the uncertainty (do I feel like this is cheating in some way? will the final work be cohesive or will it be disjointed?). Yet when I look at the little series of images I've come up with, it seems to flow well and I like the different perspectives, the emphasis on patterns, negative space, flowing lines and shapes, different textures and tones.

One problem with flowers as a subject is the fact this is a subject that's been done to death. It's overworked and difficult to make images that say anything new about flowers. They're beautiful, we know they're beautiful, we hardly need reminding that they're beautiful. Artists who've tried to find the dark side of flowers (can it even exist?) only make them seem even more beautiful. In our house my wife likes to announce "these flowers are ready for their portrait" when the cut flowers in the vase are dried and drooping (this is a joking reference to my love of such a subject). So flowers as photography subject - so cliché, so over, so done. Yet I constantly come back to them as subject matter - am I crazy to do so? I wonder.

I think this not knowing why I come back to flowers is what's causing this anxiety and uncertainty about this work. I know there's a question I'm investigating, trying to answer by making these images - but I don't know what that question is. So perhaps I've solved my dilemma - I'm compelled to make images of flowers because I'm seeking answers to an unknown question. What I do know from making these images is that I'm drawn not to the "conventional" beauty of flowers - the brilliant colours. I'm drawn to a tension between their superficial uniformity within a type, and their uniqueness - i.e. the little things that make one red tulip (for example) different from all the others. I also seem to be exploring ways to accentuate the characteristics that I personally find beautiful - those curving lines, delicate tones, the patterns within a grouping and the negative spaces defined by the grouping, formal compositional relationships between individual flowers or plants within the frame, differences in textures. Images of flowers often invoke an emotional response in viewers, and I'm learning how that response is related to these characteristics of flowers and how they are brought together in the composition. When I am photographing flowers I'm look at them as if I was drawing them, and it's those qualities of flowers I want to present to viewers of my images.

Perhaps that sounds as if I know what the question is, but I don't - I constantly return to make images of flowers, but I'm not sure exactly why. And with a bit more time to reflect on that, I'll be fine with it. I might come to like this idea of seeking answers to an unknown question.

Ten Kallitypes for a Rainy Day

Sunday, August 21, 2011

A sublime Sunday - Wet Plate and Friends

The Stone Diaries I

wet plate collodion tintype

This morning as I was drinking tea on the studio porch, I was thinking how my day might unfold: make some new tintypes; meet with a dear friend Jan for coffee; make some kallitype prints. Here's how the day has progressed so far (it's late afternoon here).

After a brief ride on the bike, I came back to find the sun full and bright in the back yard - perfect tintype conditions. I made four plates in total: two still lifes and two garden views, working in partly cloudy direct light, full on direct light and open shade. At this stage of my adventures in wet plate collodion, I like to mix and match conditions so that I become better at reading the light for determining exposure times, and also so I can get a better feel for how differences in light change the qualities (depth and contrast in particular) of the resulting images.

For the first plate of the day, I set up a table for still lifes, and picked up two rocks my wife had brought home. Elena has a strong affinity for "special" rocks and often picks up unusual examples based on shape, colours and textures. Once I saw the image on the ground glass, I imagined doing a series of images ("The Stone Diaries"), so I may well have another theme to work with as I continue to deepen my experience with wet plate. I then set up a still life with zucchini, watermelon and a half of an avocado in bright direct light:

Still life with zucchini, melon and avocado

wet plate collodion tintype

Now that I have more experience, I knew based on the still life images I made last week that I should stop down the lens for a 5 second exposure. Creases in the canvas ground provided a geometrical element to the composition that accentuates the organic shapes of the vegetables.

Finally, I did some work in open shade, making two views of the garden: the graceful bend of a japanese maple, and a rock element within the fern bed. I'm learning from these plates that open shade seems to lead to a higher contrast image:

Japanese maple

wet plate collodion tintype

Fern bed

wet plate collodion tintype

I decided to stop and clean up at that point, keeping to this principle of doing "just enough" to strengthen the consistency of my plate pouring, exposure and processing before I get to the point where I lose concentration.

A short while later, my friend Xane called to invite me over to his place for lunch with Jan. Jan is a mutual friend who moved away to Vancouver, so it's always a treat to catch up with her when she comes over to the island for a visit. Such impromptu invitations are unusual in this town, but we're all comfortable enough with each other to get together at a moment's notice. And Xane's place is a little bit of Tuscan peacefulness in the heart of the city suburbs.

We started with a throw back to our childhoods: grilled cheese sandwiches that Xane made with local cheddar and a hearty full grain bread, beans straight from the garden freshly steamed, then small sweets and watermelon. We talked about our childhood memories around food, family gatherings and picnics. After lunch I did a little show and tell of some of my tintypes and photogravure prints. Both Jan and Xane are experienced artists whose knowledge and work I greatly respect, so it was wonderful to get some feedback on this recent work from them. We finished the afternoon draped over the furniture, napping and conversing in complete relaxation.

With coffee turning into a delightful lunch and time spent in conversation, I've only just now returned home. I still hope to complete my pre-visualized day by making a few kallitype proof prints.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)